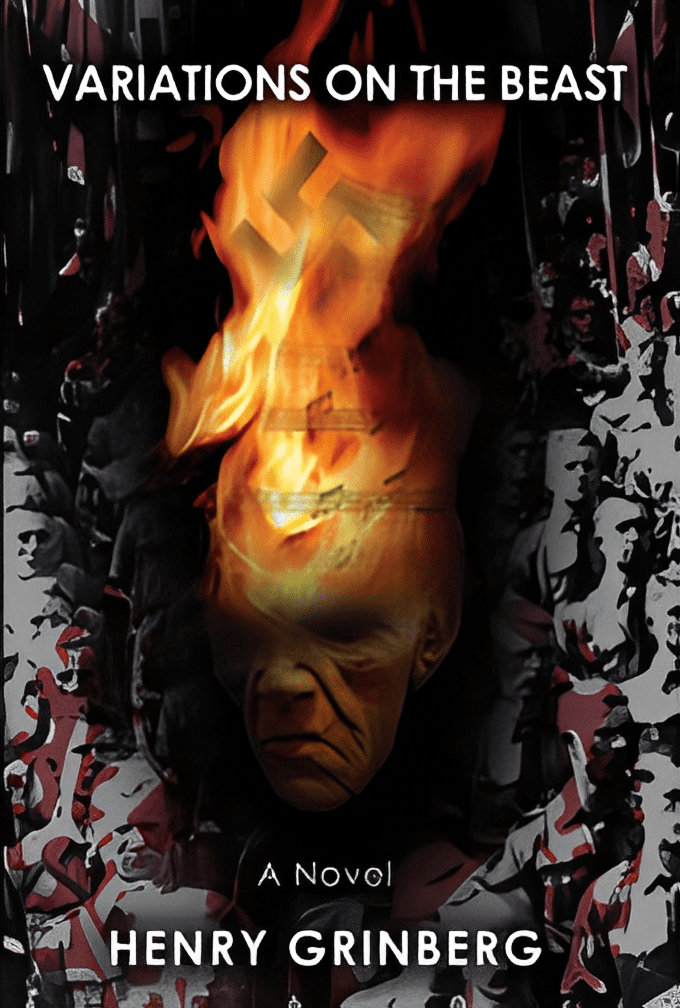

Variations on the Beast

Hermann Kapp-Dortmunder is born a bastard and a musical genius amid the grim realities of Central Europe between the two World Wars. Variations on the Beast chronicles the perverse parallel of his rise to the peak of the musical world as a charismatic conductor while the Weimar Republic collapses into the brutality of Nazism. As the twisted episodes of his life unfold, the novel's scope expands to include historical figures such as Goebbels, Göring, Herbert von Karajan, and the composer Richard Strauss, as art and fascism wrestle with each other in a world going mad.

Reviews of Variations on the Beast

Kirkus Discoveries, October 5, 2006

“A disquieting allegory for the rise and fall of man, played out in the fractured soul of a genius.”

Library Journal, by Edward Cone, January 2007

“An appropriate subtitle for this stunningly original novel would be ‘A Study in Moral Turpitude.’”

American Book Review, by Sean Bernard, March/April 2007

"Grinberg has given voice to a strange and singular narrator: a man callous, talented, ambitious."

Jewish Book World, by Shimon Gewirtz, Winter 2007

“A rich and intense portrayal of a man who becomes a moral monster while pursuing the highest levels of musical interpretation.”

The Jerusalem Post, by Tibor Kraus, January 6, 2008

“In this tale of classical music in wartime, career trumps conscience.”

The Psychoanalytic Review, by Charlotte Kahn, December 2008

“The unfolding of one individual’s character becomes the paradigm that begins to answer the question ‘How was it [the German nation’s descent into the brutality of Nazism] possible?’”

Interviews on Variations on the Beast

The New York Times

“When Great Art Meets Great Evil”

Interview in the Arts and Leisure section, Sunday, July 29, 2007

“For those who find inspiration and edification in great art, it is always painful to be reminded that artists are not necessarily admirable as people and that art is powerless in the face of great evil. That truth was baldly evident in Nazi Germany and in the way the regime used and abused music and musicians, to say nothing of the way it used and abused human beings of all kinds.

“Two new novels touch on these issues in very different ways. . . . “

— James R. Oestreich, The New York Times

NPAP Authors

(from News and Reviews, the National Psychological Assn. for Psychoanalysis quarterly newsletter, December 2006)

An Interview with Henry Grinberg

by Jim Rubins

NPAP member Henry Grinberg has just published a novel, Variations on the Beast (The Dragon Press, NY, 2006). It follows the career of a genius conductor in Germany and Austria, Hermann Kapp-Dortmunder, from the pre-war rise of Nazism, through the war, and into the post-war period. We spoke with Henry about his book shortly before its release on December 16.

JR: You love music and hate Nazism. Why bring them together in this novel?

HG: I’m fascinated by the contrast between the superb levels of culture in Germany, joined with the capability for such incredible cruelty. Hannah Arendt’s concept of “the banality of evil” provided a new profound truth; until then, the Nazis had been thought of only as monsters, but they were not. Many, for example, went home every night to their wives and children. Still, it is the unanswerable question: How did the Germans come to commit bestiality and to tolerate it?

JR: You explore that question from the vantage and experience of Hermann. What is his experience, as you tell it?

HG: Throughout his life he makes choices of convenience, which turn out to be Faustian bargains. He is a spiritually homeless man, making a way for himself in the world, and he calls upon examples that he has witnessed in his elders, who taught him not to reason but to brutalize and crush. His father and his music teacher got their way by screaming and brutalizing. Hermann has been subjected to this, and so he adopts it. He is gifted as a great musician but is also, unhappily, a moral monster who brings harm and even death to people who care about him. All human beings are capable of bestiality, and we have to watch ourselves.

JR: What are the personal referents, for you, in this book?

HG: I was born in England and was there during the war. I was 9 years old when it started and have always been conscious of what happened in Europe in that period. Some of my family perished there. And I’m aware of what a close call we had in England, not just the bombing, but the Germans were only 20 miles away, across the Channel. My blood still runs cold when I think about it. What if? As Jews, we would not have survived.

JR: It seems curious that you choose a thoroughly despicable, anti-Semitic character as protagonist. Is there something of you in Hermann?

HG: Yes, something of me. I remember a phrase from my childhood, “schlug’m nisht” (“don’t hit him”), uttered by concerned uncles and aunts. My father was a harsh man, born in Russia. I developed an early facility for fibbing to get myself out of scrapes. Both Hermann and I are the kind of person who prefers the way it should have been to the way it is—a willingness to alter reality to suit a preferred scenario. And of course there is always an element of themselves in whatever fiction authors produce. When Flaubert was tried for insulting the French nation in writing his great novel, he said “Madame Bovary, c’est moi.”

JR: How did you research the book?

HG: During the writing I had two impulses. The first was to read general histories, for instance about Jewish culture in the Nazi period, and to use maps and guidebooks to pin down geographical entities and be factually accurate. The other impulse was to stay away from individual accounts like biographies so as not to be swayed by anyone’s life or opinions. And I deliberately did not read Thomas Mann’s Doctor Faustus, not to be swayed by that, and of course to avoid plagiarism. Now that the book is finished I’ve discovered many fine things about this period, for instance a film about Furtwängler, the conductor, being interrogated for possible war crimes.

I’ve always been a voracious reader, taught English for 42 years in college, and so it was natural to try my hand at writing. A serious component of writing fiction is the ability to alter facts, particularly if by doing so, I may reach a deeper truth. If I’m lucky, I’ll find an audience for my untruths.

JR: What’s a “lie” in this context?

HG: As I say, a factual untruth, an exaggeration of colors and flavors, so it no longer represents the facts. A romantic novelist frames a universe where passion seems all-consuming; a political novelist exaggerates something else. When people read these novels, they feel they’re truthful. The most fortunate writers address the reader in a way that makes the reader feel embraced, understood, and apprehended. Conrad and Dickens do that for me.

Conversation about Variations on the Beast

Variations on the Beast is an intriguing title. What does it mean?

It presents the different sides of my principal character, Hermann Kapp-Dortmunder—a highly gifted musician and a great orchestral conductor, one of the giants. I follow him at a particular period of history: Germany before, during, and after the Nazi era. My great musician is not only gifted but also, unhappily, a moral monster who brings harm and even death to people who care about him, including the women who love him.

How does your great artist manage at the same time to embody the beast of your title?

The novel is set in Nazi Germany and Austria. One of the agonizing questions I struggle with is this: How did the Germans, who proclaimed themselves the most educated, cultivated, and law-abiding nation on earth—the nation of artists, thinkers, and scientists—come to commit bestiality and to tolerate it? I am tortured by this unanswerable question to this day, 60 years after the events.

What does Hermann’s story have to do with that phase of German history?

Hitler’s perverse genius lay in harnessing German hatred and resentment, which gripped the entire nation following the collapse of 1918. He claimed that German blunders were not responsible for that defeat; it was the Jews who stabbed the Germans in the back—the capitalists of the West and the Bolsheviks of the East. The other principal so-called Jewish crime was the wish to pollute German racial purity. Hermann does not officially become a Nazi party member—like the conductor Herbert von Karajan, for instance—but he goes along with party doctrine for the sake of convenience and personal enrichment.

What was it like for you as a Jew to speak in the first-person voice of a character so thoroughly anti-Semitic?

It’s not an easy question to answer. On one level, the Nazis were and are an abomination, murderous and hateful beyond compare. But I am a scholar, a psychoanalyst, and a writer. I feel impelled to study how in the world such people originate and develop. The Germans may have been led by psychopaths, but were all of them mentally ill?

I have a reverence for art and music, and perhaps a naïve faith that art makes us better human beings. I am faced with the awful fact that distinguished and revered figures throughout Germany rationalized living in a nation that committed horrors as a deliberate choice. Some Jewish artists, musicians, and writers managed to leave Germany. Those who did not perished or suffered horribly, as did Jews throughout occupied Europe. Many non-Jews refused to tolerate Hitler and also left.

In this novel, I follow closely one of the majority who remained. I describe how he justifies himself, how he behaves, and most important, what he does not question.

Hideous crimes like these still take place. The questions must still be asked.

Testimonials on Variations on the Beast

Product Details

Rights and inventory have reverted to the author.

To order Variations on the Beast at a 50% discount + shipping,

please click here.