From Hackney Downs Boys in Wartime, 1939–1945, An anthology of the Grocers’ School’s experience, edited by D.B. Ogilvie and G.E. Watkins (The Clove Club, MMV, 2005)

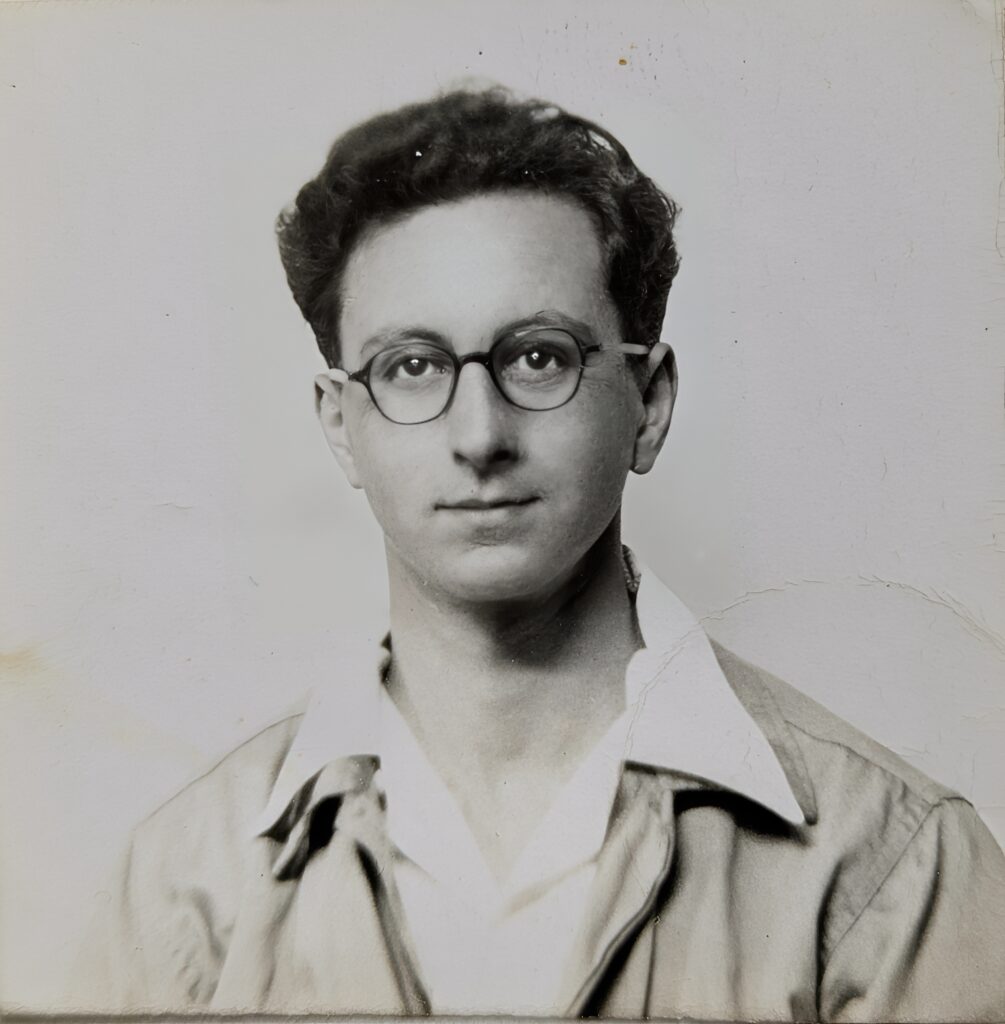

HENRY GRINBERG (1943–1948)

King’s Lynn stands out, like many youthful shaping memories, as a major prominence in a string of places and events in my life as an English teenager during the Second World War. That war began when I was nine years old and ended when I was 15. I thanked heaven every day for the accident of my English birth, thus avoiding the fate of European Jews, including members of my family, who were murdered by the Germans. But, not to draw disrespectful comparisons, life was eventful enough, what with massive bombing attacks, threats of invasion, heartbreaking losses, and disruptions of life.

King’s Lynn meant, first of all, another year among strangers. In response to various emergencies, I had already been shuttled back and forth among London, North Wales, South Wales, and nearer home, Amersham, Bucks. My parents in Stamford Hill lamented that my education was in tatters: no continuity or cohesion. In 1943, at 13, at a makeshift school in Dalston (no, not that one), I was euchred into sitting for an exam that, I was told, might secure me a secondary education. To the astonishment of my parents, I passed, one of only two boys in the entire school to do so. I became a Fourth Former at the Hackney Downs School Tutorial Classes, as the enterprise was then known, a manageable 653 trolley-bus ride from home.

But not for long. The bombing, which had seemed to die down after the London Blitz of 1940–41, picked up again, but not as ferociously. Even so, I remember scary times, interrupted classes, boys trouping en masse to the school’s air raid shelter, and uncomfortably close loud bangs. Then the V1s began to appear, the Doodlebugs, the pilotless planes. Now the sirens didn’t bother to sound at all; we were in a state of constant alert. When you heard one of the things approach, you didn’t need to be told to duck into the cellar or a street shelter until you heard an explosion. Then, if you lived, you resumed your activity. Soon after came the V2s, the first ballistic missiles. They traveled faster than the speed of sound. First, you heard the explosions, then the sound of them roaring at you through the air. That is, again, if you were not hit. In the summer of 1944, at 14, I was sent to King’s Lynn to join what was considered the main school.

That was how I first met our headmaster, Mr. T. O. Balk, who was based in Lynn and who had had many years of experience running a smooth operation at a school in exile, as it were. In London, Mr. T. B. Barron, the kindly deputy head, may have led us at the venerable school building on Downs Park Road, but TOB exuded a sense of crisp, no-nonsense authority. The new arrivals were squared away in billets with dispatch, and I joined the classes that were conducted at what I think had been a technical school on Birchtree Close.

I didn’t know then that I would gain the dubious distinction of being billeted on four (repeat, four) separate families in the space of one short year. Unfortunately, over the nearly 60 years since the war, my memory is no longer secure. I’m secure with places, occasions, and events, but no longer with all the names of people I knew. My first new family turned out to be a pleasant older couple who lived in a small house on Wootton Road, three or four miles from the center of town, on the way to Castle Rising. They had two grown-up daughters, one a bus conductress who lived with us and the other in war work, who came home once every month or so. I was their first “vaccy,” and they certainly treated me warmly. My new “Dad” was a farm overseer on the vast, flat sugar-beet fields they have in that part of Norfolk. He immediately took to me and intimated he enjoyed having a son. This was a new experience because my own father, though loving, I’m sure, was usually gruff and distant. My King’s Lynn dad was an enthusiastic member of the local Home Guard and sometimes took me with him on Sundays to the firing range, where he liked to introduce me to the others as his son. He urged me to join the battalion of the Army Cadet Corps, attached to the School, and which was affiliated with the Royal Norfolk Regiment. That battalion was commanded by Mr. Moody, who taught history, mild of manner but tough of mind, with second-in-command Mr. Thomas Prosser Thomas, who taught us geography and always seemed to breathe fire.

Because of his military connections, my “Dad” secured for me smart-looking boots, puttees, a snappy belt, a forage cap that fit, and other accoutrements that gratified my vanity if they did not always meet regulations. He was an old soldier of the First World War and imparted to me the vital importance of brightly gleaming buttons and badges and of a freshly blanched web belt. My new mom also spoiled me by waking me up each morning with a cup of tea and a margarined crumpet, a coddling also completely new. That practice ended the day I was trying both to manage a filled cup and to sneak in a few pages before school of Gone with the Wind, a massive volume, which I had discovered in their house. I tipped over my cup and soaked the bedding—an event, Mum assured me, that had no bearing on their decision, some five months later, for me to have to leave. I hoped that was true.

During the first week, I made my way to school by bus. Then I received a letter from my parents in London, informing me that they had purchased a bicycle for me, which would arrive the next day on the train. That was another surprise because my father had often asserted that I was too dim-witted and ungainly ever to manage a bike. But when I turned up at the station, there it was, a handsome B.S.A. “tourer,” wartime utility model (i.e., all black paint, no chromium), waiting for me outside the stationmaster’s office. Of course, by then I had been riding a bike for years, but my father had not officially recognized it. I was thankful for his change of heart. Now I was able to go everywhere swiftly and safely. I have been living in New York City for the past 53 years. Attitudes toward cyclists here are completely different from what I remember in England. By and large, motorists there were considerate. In contrast, New York motorists regard cyclists as legitimate prey, entitled to no courtesies whatsoever; consequently, many cyclists ride on the pavement, to the peril of pedestrians. A bad situation all around.

But now I was free. It was the best of all possible worlds. I had mobility and, at 14, freedom from parental control. I was hardly the wild animal that my parents frequently alleged, but I indeed asserted my independence. King’s Lynn represented another step in my particular wartime experience, another prolonged absence from home, as I have described. I was something of a solitary in those days. So for a while, I did my riding alone. One of the places to catch my attention was Castle Rising, the ruins of an old Norman castle, farther north along Wootton Road. It fascinated me. We who grew up in England were used to the presence of historic sites, venerable buildings, palaces, and antiquities of every description. The Tower of London and I were old friends, and, because my father worked close by, I liked to frequent St. Paul’s Cathedral and join the tours whenever I could. Inevitably, I came to memorize what the guides had to say at each spot. I’m sure I drove them not a little crazy as they conducted us around the memorials, through the crypts, and up into the Whispering Gallery. I used to murmur their little speeches along with them. I took a similar proprietary pleasure in Castle Rising. For one thing, it was close by, and as I was new to Lynn and somewhat slow to blend in with my schoolmates, I must have sublimated initial loneliness in those ruins. Soon enough, I became caught up in school routines, but for a while, it pleased me to commune with the castle.

Castle Rising was awe-inspiring. The rectangular keep was built of massive, rough gray stone blocks—when I knew it, it was badly in need of restoration. I don’t think one was permitted to enter the structure in those days, but I could walk around the keep. There were few visitors, and I often had the place to myself. I suppose I was intoxicated by its antiquity—said to date from the twelfth century—and quite in line with my own pompous sense of descent from an ancient people. The castle was surrounded by a moat, dried-up up, of course, and inside that, by tremendous sixty-foot-high earthworks, some said dating back to the Romans. I loved the place.

At quite another geographical extreme, a favored place to cycle was along the bank of the River Great Ouse, as the waterway is officially known. Again, usually alone, I biked past the Fisher Fleet inlet, rich with briny smells of catches ancient and modern, the fisher crews laughing, smoking, and talking at the end of the day, repairing nets, and snacking on cockles, winkles, and whelks. I rode out downriver to The Wash, as far as I could go. I enjoyed the solitude of the empty Fen Country, covered with reeds and rough, coarse grass that, if you sought to grasp, could open nasty gashes on the palms of the unwary. The Wash presented itself sometimes as a gray mud flat, stretching for miles, accompanied by the lonely soughing of wind together with the incessant cries of seabirds. With the tide in, the water seemed almost to lap at one’s feet. Once, while communing with the sea, I thought of King John, who attempted to cross The Wash at low tide, only to be caught by rising floods and ended up losing the Crown Jewels of England. Surely a man of disappointments: not only having to endure Magna Carta, but also that calamity. Sometimes I would espy a grim grey destroyer, its serial number large on its bow, beating its way slowly down the estuary, perhaps departing on patrol. I wished it Godspeed.

Demands of the classroom finally overtook my reveries. My Fifth Form Master was Stanley Day, known unofficially as “Daisy,” a precisionist who instilled in me a love of poetry, particularly Shakespeare, and a man of deadly aim with a hurled piece of chalk. For some reason, nobody lost an eye. But if a boy’s attention should wander from the text of King Harry’s speech before the gates of Harfleur, he would be sure to be zinged—in addition to suffering the humiliation of being requested to return the chalk to Mr. Day. I remember one of my classmates, Martin Gis, whom I thought unusually canny and wise, because he not only knew when a piece of chalk was coming his way but was also able to move his head aside and cause some luckless innocent next to him to be struck. Mr. Day used to refer to Gis as “the Prince of Darkness.” Not until later, after I had read Dante and Milton, did I realize that “Daisy” was perpetrating a dreadful pun, playing on Gis and Dis, the mythological king of the underworld. Mr. Day kept you alert and made books vital. He was also active in the local theater and, while I was there, staged a wonderful production of Shaw’s Arms and the Man, himself taking the richly ironic role of Captain Bluntschli. He was blunt and outspoken, but as far as I could see, always good-humored, without a trace of malice. I was impressed by the number of older boys, Sixth Formers, who sought his approval and trusted his judgment. Mr. Day had founded the school’s Literary and Debating Society. I was happy to be accepted as a member but didn’t dare open my mouth. These older boys were clearly superior beings, not only knowledgeable but outright learned. And so devastatingly witty. Models to emulate. Even though we’d had a full day of school, it was a pleasure to reassemble after tea for an evening of unstaged play-readings or engaging in formal debates, which I remember being taken very seriously, and I’m sure, for some, a proving ground for the Oxford Union, if not the House of Commons. I also joined the Music Club, which I think met weekly, and deepened, via its collection of massive 12-inch 78-rpm records, my passion for classical music. One of my classmates, Stanley Harris, used to place posters on the Music Club door posters, which he had himself painted, illustrating the week’s music, whether symphony, opera, or ballet. They were very good, and Harris didn’t seem to mind when I laid claim to some of them.

Another master I remember was Mr. Gee, who taught us science, a subject for which I also developed a kind of passion, particularly biology. I was somewhat put off by Mr. Gee because he, in contrast to Mr. Day, never seemed consistent in his reactions to the boys—one moment encouraging, the next cold. He sometimes took charge of us at football, inevitably on muddy, rain-soaked days. He would oversee the choosing of sides and act as referee, stalking up and down the field draped in a baggy coat, an impossibly long scarf wound several times around his neck, smoking a pipe, and peering at us owlishly through horn-rimmed glasses. One day, obviously bored, he suddenly uttered a wild cry and charged at us. He tackled the center-forward, deprived him of the ball at his feet, reversed direction, and, quite alone, scored a goal for himself, all the while whooping with glee. The next instant, he had retreated within himself again.

A third master was Mr. Fox, who taught math, at which I was hopeless. Of all the things I feared in life, arithmetic, algebra, and geometry took first place. It has always been thus since I was a small child. If I didn’t have ten fingers to rely on, I would have been truly lost. Threats, wheedles, deprivations, and enticements of all kinds were useless. Thank heaven, Mr. Fox sometimes interrupted his attempts to pound numbers into us to discuss the war. I particularly remember his talking to us about the operation known as Market Garden in late September 1944. British and U.S. ground and airborne divisions had been confident that they could end the war early by driving across the Lower Rhine and other rivers in the area to penetrate the industrial Ruhr. Unhappily, the British Sixth Airborne Division became stuck at Nijmegen, the point of farthest penetration, causing the entire plan to fail. The losses were sobering to Allied hopes. But Mr. Fox also spoke to us about more successful campaigns.

Little by little, I settled in. I discovered the fascinating side streets and lanes of King’s Lynn, in addition to the open plazas of the Tuesday Market Place and the Saturday Market Place, both of which bustled with a profusion of livestock and produce on the appropriate days. And I was very comfortable with the ambience, as one would call it today, of locales like New Conduit Street, Purfleet, Greyfriars Tower, the museums, and the library. I appreciated the town’s human dimension compared to what I perceived as a lack of soul in large cities. Above all, I discovered, though it appeared in no guidebooks that I knew, that King’s Lynn rejoiced in the possession of possibly more fish and chip shops per acre than any other place I know, all of them excellent. There is nothing to compare with a succulent, crackling piece of fried codfish and a generous mound of chips, laced with salt and vinegar, wrapped in a sheet of newspaper. But even greater than that pleasure, King’s Lynn brought me at 14 my very first girlfriend, chaste and pure though that association was. Once or twice a term, the school arranged dances with neighboring girls’ secondary schools, discreetly chaperoned by TOB and the headmistress concerned. Shy as I was, I managed to make the acquaintance at one of those dances of a pretty young charmer. She was also 14 and as nervous as I. We never became what you might call a regular couple—I felt much too jumpy to ask that—but we did go out walking, staring fixedly ahead in utter silence because neither of us could think of a thing to say. We bought fish and chips and consumed them during nervously rapid hikes along the banks of the Ouse. I was intensely curious about how girls think, feel, and function, but even constant attendance at American films, which for many of us was an academy in the arts of living, failed to instruct me in the protocols of opening moves. I would have needed the cinema of a later age for that. Just as well.

After five happy months living on Wootton Road, my “Mum and Dad” announced that their daughter, who worked in a munitions factory up North, was being transferred home and that they would need my room for her. Sadly, I said goodbye and was next billeted with a very aged, but spry, old lady who lived right in the old part of town. She already had an evacuee with her, Monty Lubich, a fellow Hackney Downs pupil, a year or so older than I, who properly regarded me with lofty disdain. My new “lady” was glad to have another “vaccy,” principally, I think, because she relished pork pies, which she made herself. My ration book, added to hers and Monty’s, ensured the purchase of sufficient pork for impressively large pies each Sunday. I don’t remember if Monty ate his helpings, but I was certainly unable to. I was too close to Hebrew school to do that. Perhaps I could manage non-kosher beef or chicken. But pork? Never.

Within six weeks of my arrival, that lady unfortunately fell ill, and both Monty and I had to present ourselves at TOB’s study to inform him that we needed new billets. I remember him looking somewhat quizzically over his glasses when he saw me again so soon, but the presence of Monty, obviously in the same boat, saved me from undue scrutiny. My next billet provided a somewhat exotic experience. Once again, I found myself on Wootton Road, but closer to town. I stayed in the house of the transplanted London mother of two HDS boys. Hers is the only King’s Lynn billet name I remember, but because our relations were so stressful, I think it wise not to reveal it. In addition to her own two HDS sons, there was another HDS evacuee in the house, Cyril Kopkin, with whom I was surprised to learn I was to share a bed. Within two weeks, whether I was responsible or my bedmate, we had both developed nasty rashes and were spending much time scratching. I must have informed my mother because the next thing I remember was that she had come to Lynn, taken me to a doctor (who diagnosed a severe case of scabies, luckily easy to treat), requested an audience with TOB (dragging me along with her reluctantly to his home), and demanded another new billet for me, my fourth in the space of a single year. By now, it was springtime, 1945, and the war looked as though it might be over soon. The Battle of the Bulge, Hitler’s last gamble in the West, had failed; Eisenhower’s and Montgomery’s armies were fighting on German soil; and the Red Army was pushing closer to Berlin.

My final billet was with a friendly mother of three young children living somewhere in the estates south of Gayton Road; I don’t remember exactly where. Her husband had been a prisoner of war since before Dunkirk and had been held by the Germans for five years. But, she told me, letters reached her regularly, and the War Office said he had been located and would be coming home soon. My final two or three months in King’s Lynn were uneventful. The weather was improving. I continued to walk out with my girlfriend, as usual, not saying much to each other, without our seeking greater intimacy—and I was surprised that my schoolmates joshed me about that—but she and I were content with that. With the impending end to the war, there was talk of a general election, and I was amazed to hear among the ordinary people of Lynn that they didn’t want Winston Churchill to continue as prime minister. He had been wonderful in war, they said, but they didn’t want a Conservative government.

In May, the school was holding a sports day, at the end of which TOB, while awarding certificates to the winners, announced that the war in Europe was over. “Tomorrow is VD Day,” he said solemnly, only hastily to correct himself: “I should say VE Day.” [i.e., Victory in Europe Day rather than Venereal Disease Day. Venereal diseases were constantly in the news, presented to us as definitely the worst of wartime scourges.] But everybody merely chuckled at this uncharacteristic slip from this uncommonly meticulous gentleman. There were jovial, neighborly open-air parties all over King’s Lynn. In the morning, I rode through the streets on my bike with a Union Jack pinned to the front of my shirt and the Stars and Stripes and the Soviet flag pinned to my back. I was cheered lustily wherever I appeared. Some days later, there was a victory parade in which the school’s battalion of the Cadet Corps participated. Very moving and exciting.

Our time in King’s Lynn was coming to an end. The man of the house at my final billet returned home from a prisoner of war camp. I don’t think he was delighted to see me, but, assured that I was shortly returning to London, he said little. The school term was over, and the evacuees were marking time until they left. In the meantime, friends informed me that I could earn a few bob at pea-picking. That sounded like fun, so I rode out to the fields with them and joined scores of itinerant workers, gypsies, and other casuals who squatted their way down the rows. At first, it was hard to get the hang of it, but I watched the people in the next row. The trick was not to pick the peas one by one, but to wrench the entire vine out of the ground, hold it upside-down so that the peas dangled freely, and then they might be easily stripped and stuffed into the huge hemp sacks we dragged along behind us. By the end of each afternoon, I had filled two sacks and was paid three shillings and sixpence for each. By the fourth day, these fields were emptied, and I thought it too much to bike farther out in the country to find more.

One day, a bunch of us, including Henry Woolf, had come from playing football when we met a group of yet-unrepatriated German prisoners of war. They were under the casual, unconcerned supervision of an elderly member of the Home Guard. My heart burned with hatred at the sight of them, looking so tanned and healthy from whatever work they had been doing, obviously wholesome and outdoors. News had been reaching us of mass murders and of the human wreckage discovered in the concentration camps. The prisoners called out to us to pass the balls to them, indicating that we could kick them back and forth until their lorry arrived. We were all to be friends again. Their guard smiled benignly. I said nothing at the time but felt distinctly ill.

Within a few days, we were on the way home. My parents had written that they wouldn’t meet me at Liverpool Street station, but that I might ride my bike home to Stamford Hill, which I accomplished safely. In 1956, eleven years after the war, now 26 and a resident of New York City, I revisited, taking a bicycle trip through southeast England by way of Saffron Walden, Cambridge, Ely, and Downham Market, finally arriving at King’s Lynn in easy stages. I fulfilled a long-yearned-for desire by booking a room at the Dukes Head Hotel on the Tuesday Market Place. I discovered most of my old friends and generous hosts to be in good health and in good humor, but far more plump than I remembered. Furthermore, I have not visited since then.